THE NBC

PACIFIC

COAST

NETWORK

Copyright 1997 by John F. Schneider,

Seattle, Washington

INTRODUCTION

The period of the 1930s and 40s has been appropriately called "Radio's

Golden Age." During these years, the nation was entertained and

informed by a host of live coast-to-coast network broadcasts. Radio

historians have correctly identified the importance of New York,

Hollywood and Chicago as network production centers during these

years. However, little has been said about the role played by San

Francisco.

The decade from 1927 to 1937 can easily be termed San Francisco radio's "Golden Decade". It was during that ten-year span that San Francisco was a major origination point for many nation-wide network broadcasts, and that both NBC and CBS maintained production centers there.

THE NBC "ORANGE" NETWORK:

Early network broadcasting activities in the United States emanated from

stations in New York City, and primarily served only the northeastern states.

AT&T operated the first active network in the country from its flagship

station WEAF, beginning in January of 1923. The first coast-to-coast

broadcast took place in 1924, with KPO in San Francisco representing the

western terminus of the effort. The most far-reaching of these early

activities was on March 4, 1925, when AT&T arranged the broadcast

of the Calvin Coolidge inauguration to a nationwide hookup of 22 stations.

(The early network broadcasts to the West Coast were temporary, however,

with connections made over ordinary voice-grade phone lines.)

The RCA Corporation also operated a more limited network operation in 1923 from its station WJZ. The broadcasts were transmitted over Western Union telegraph lines, which proved inferior to AT&T's telephone network. (AT&T maintained for itself the exclusive right to network operations over telephone lines, and would not lease its lines for this purpose to any other entity.)

In 1926, an agreement was reached between AT&T and RCA which would have a far-reaching effect on the business of broadcasting. This agreement resulted in AT&T's withdrawal from the broadcast business, and the sale of its stations and network operations to RCA. Also included in this document was an agreement by AT&T to lease its phone lines to RCA for network broadcasting purposes. RCA formed a new corporation on September 9, 1926, known as the National Broadcasting Company. The new company was owned by RCA, as well as two of its parent companies, Westinghouse and General Electric.

NBC's first broadcast on the WEAF network took place November 15, 1926. On January 1, less than two months later, a second NBC network was inaugurated, originating from WJZ. To distinguish between the two separate telephone-line networks, AT&T technicians used red designators at their jack panels for the original network's connections, and blue designators for the newcomer. The names of these two networks were casually derived from these colored cables, so that the WEAF group became known as the Red Network, while the WJZ group was called the Blue Network.

In the beginning, NBC was "National" in name only, as its programs reached only as far west as Denver. In its first years, NBC was unable to set up a coast-to-coast hookup. AT&T had not yet installed broadcast quality telephone lines across the Rocky Mountains.[1] To alleviate this problem, the NBC Board of Directors voted on December 3, 1926, to establish a third NBC network: the Pacific Coast "Orange Network".[2] They assembled a full duplicate of the New York program staff in San Francisco, and the Orange Network began originating programs for seven Pacific Coast stations: KPO and KGO in the San Francisco Bay Area, KFI Los Angeles, KFOA Seattle (later the affiliation changed to KOMO), KGW Portland, and KHQ Spokane. The seven stations were connected by 1,709 miles of telephone lines.[3]

The inaugural program for the NBC Orange Network was held April 5, 1927, less than five months after the first NBC broadcast in New York. The program originated from temporary studios in the Colonial Ballroom of the St. Francis Hotel, as permanent studios in the new Hunter-Dolin Building were not yet ready for occupancy. The program opened with an address by Henry M. Robinson, the Pacific Coast member of the NBC Advisory Board and president of the First National Bank of Los Angeles. Robinson spoke from the studios of KFI in Los Angeles. The program was then turned over to San Francisco for the broadcasts of music by Alfred Hertz and the San Francisco Symphony, and by Max Dolin, the newly-appointed West Coast music director, conducting the National Broadcasting Opera Company.

On April 11, the network began regular broadcasting with the program "Eight Neapolitan Nights", sponsored by the Shell Oil Company. The initial network schedule was 8 to 9 p.m. Monday and Saturday, and 9 to 10 p.m. Tuesday through Friday, giving the network a total of six hours of programs weekly.[4] (At first the networks operated only in the evenings because circuits could not be spared from the standard telephone service during the busy daylight hours.[5])

The Orange Network recreated the same programs heard in the east on the Red Network. At the conclusion of a program in New York, all of the program continuity, including the scripts and musical scores, would be shipped to San Francisco by Railroad Express, where it would be rehearsed for performance exactly a week later. Thus, the San Francisco cast was producing such well-known early network shows as "The RCA Hour", "The Wrigley Program", "The Standard Symphony Hour", "The Eveready Light Opera Program", "The Firestone Hour" and many more. At the conclusion of each program the announcer would say, "This program came to you from the San Francisco studios of the Pacific Coast Network of the National Broadcasting Company." This would be followed by the traditional NBC chimes. The chimes were a part of all NBC programs from the very beginning; however, they were considerably longer and more involved than the later three-note chime. Because they were so long and clumsy, they were shortened to the well- known G-E-C progression heard today. It is said that the notes G-E-C stood for the "General Electric Company", a melodic tribute to one of the network's major parent corporations. The original NBC chimes were struck by hand, but they were replaced in the mid-30's with electronically-produced, perfect-pitch chimes.[1]

Shortly after the Orange Network's inaugural broadcast in 1927, the

staff moved into its permanent headquarters in the new Hunter-Dolin

Building, at 111 Sutter Street. The NBC studios occupied the entire

22nd floor, while the network offices were located on the second

floor. The studio complex included three completely-equipped studios

and an elaborate new pipe organ. It was in these studios that most of

San Francisco's "Golden Decade" programs would originate. The entire

NBC complex was decorated in a Spanish motif; one of its more unusual

features was a glass-enclosed mezzanine, decorated to resemble a

Spanish patio. It was designed so that a small audience could watch

the programs while they were being broadcast. Some of the heaviest

users of the booth were the sponsors of the programs, and this

experience sparked the establishment of sponsors' booths in network

studios across the nation.[1]

Shortly after the Orange Network's inaugural broadcast in 1927, the

staff moved into its permanent headquarters in the new Hunter-Dolin

Building, at 111 Sutter Street. The NBC studios occupied the entire

22nd floor, while the network offices were located on the second

floor. The studio complex included three completely-equipped studios

and an elaborate new pipe organ. It was in these studios that most of

San Francisco's "Golden Decade" programs would originate. The entire

NBC complex was decorated in a Spanish motif; one of its more unusual

features was a glass-enclosed mezzanine, decorated to resemble a

Spanish patio. It was designed so that a small audience could watch

the programs while they were being broadcast. Some of the heaviest

users of the booth were the sponsors of the programs, and this

experience sparked the establishment of sponsors' booths in network

studios across the nation.[1]

affiliates, were hardest hit, and as the network schedule was expanded

this process continued. One of the most popular KPO personalities to

make the move was Hugh Barrett Dobbs, who moved his "Ship of Joy"

program to the network, where it became the "Shell Ship of Joy",

sponsored by the oil company of the same name. Another person to make

the move was Proctor A. "Buddy" Sugg, who came to NBC from KPO as a

technician and gradually moved up the ladder until he became the

nationwide executive vice president of NBC.[1]

affiliates, were hardest hit, and as the network schedule was expanded

this process continued. One of the most popular KPO personalities to

make the move was Hugh Barrett Dobbs, who moved his "Ship of Joy"

program to the network, where it became the "Shell Ship of Joy",

sponsored by the oil company of the same name. Another person to make

the move was Proctor A. "Buddy" Sugg, who came to NBC from KPO as a

technician and gradually moved up the ladder until he became the

nationwide executive vice president of NBC.[1]During the first few years of operation, program announcements were made by actors, musicians, or generally whomever was available. However, as the staff continued to grow, the first full-time staff announcer was hired. He was also borrowed from a local station, and Bill Andrews moved from KLX in Oakland to NBC in 1928. Other announcers followed: Jack Keough came from KPO; Jennings Pierce was recruited from KGO; Cecil Underwood was imported from affiliate KHQ in Spokane. Many others were gradually added until there were seventeen at the height of the operation. Andrews became chief announcer in 1933.[1]

The entire NBC-Pacific operation was headed by Don E. Gilman, vice

president in charge of the Western Division. Gilman had been

recruited from a local advertising firm to manage the operation in

1927. Prior to that time, he had been one of the best-known

advertising men in the West, and had been president of the Pacific

Advertising Clubs Association.[7]

The entire NBC-Pacific operation was headed by Don E. Gilman, vice

president in charge of the Western Division. Gilman had been

recruited from a local advertising firm to manage the operation in

1927. Prior to that time, he had been one of the best-known

advertising men in the West, and had been president of the Pacific

Advertising Clubs Association.[7]

Initially, although the network provided several hours of programming to its affiliates, it otherwise had little impact over the day-to-day operations of the stations. KGO was operated by the General Electric Company, and KPO by Hale Brothers Department Store together with the San Francisco Chronicle. This changed in 1932, when NBC leased the licenses and facilities of both stations (they were later purchased outright). When this happened, the program staffs of KGO, KPO and NBC were combined into one collective staff of over 250 persons. This included complete orchestras, vocalists and other musicians (there were five pipe organists alone), and a complete dramatic stock company. The entire operation was consolidated under one roof at 111 Sutter Street. It was there that all programming originated for the network, which then averaged about fifteen hours a week, as well as local programs for KGO and KPO. As a result, these stations lost their independent identities, except for their separate transmitter facilities.[1] (KGO operated at 7,500 watts from a General Electric factory in East Oakland. KPO transmitted from the roof of the Hale Brothers Department Store with 5,000 watts until 1933, when a new 50,000 watt facility was constructed on the bay shore at Belmont.)

EARLY NETWORK PROGRAMS

The old KPO studio at the department store continued to be used for

just one NBC program, "The Woman's Magazine of the Air", with host

Jolly Ben Walker. This was a morning home economics show popular in

the West for many years. Reportedly, the first bona fide singing

commercial -- that is, one sung for the sole purpose of praising a

product -- was heard on this program. The commercial was for

Caswell's National Crest Coffee, and, according to Bill Andrews, "went

something like this":

The old KPO studio at the department store continued to be used for

just one NBC program, "The Woman's Magazine of the Air", with host

Jolly Ben Walker. This was a morning home economics show popular in

the West for many years. Reportedly, the first bona fide singing

commercial -- that is, one sung for the sole purpose of praising a

product -- was heard on this program. The commercial was for

Caswell's National Crest Coffee, and, according to Bill Andrews, "went

something like this":

Coffees and coffees have invaded the West,

but of all of the brands, you'll find Caswell's the best.

For good taste and flavor,

you'll find it in favor.

If you know your coffees,

buy National Crest.[1]

Some of the other programs that originated from 111 Sutter Street

during these years were "Don Amaizo, the Golden Violinist", who played

for the American Maize Company (the musician who performed for West

Coast audiences was Music Director Max Dolin); "Memory Lane"; "Rudy

Seiger's Shell Symphony", broadcast by remote from the Fairmont Hotel;

"Dr. Lawrence Cross"; and the "Bridge to Dreamland", originated by

Paul Carson and consisting of organ music by Carson intermixed with

poetry written by his wife.[1]

Throughout all of these programs, even though the performers went unseen by their radio audiences, NBC required formal dress. This meant that actors and announcers wore black ties, actresses wore formal gowns, and musicians wore uniform smocks, with the conductor in tie and tails. This was done for appearance, in the event that the sponsor or some other important person should drop in unannounced.[1]

NBC GOES 'TRANSCONTINENTAL'

Until September of 1928, there was still no such thing as a weekly

"coast-to-coast" network program. Even then, the connection between

Denver and Salt Lake City was a temporary one made by placing a long

distance telephone call. Eleven sponsors reached the Pacific Coast

with their programs using this method for a few months. AT&T finally

completed the last link in the broadcast quality telephone network in

December of that year. The first program to use the new service was

"The General Motors Party" on Christmas Eve, 1928. Regular

programming began shortly thereafter, and western listeners could now

enjoy the original eastern productions for the first time. NBC now

boasted a nationwide network of 58 stations, with the potential to

reach 82.7% of all U.S. receivers.[8]

Until September of 1928, there was still no such thing as a weekly

"coast-to-coast" network program. Even then, the connection between

Denver and Salt Lake City was a temporary one made by placing a long

distance telephone call. Eleven sponsors reached the Pacific Coast

with their programs using this method for a few months. AT&T finally

completed the last link in the broadcast quality telephone network in

December of that year. The first program to use the new service was

"The General Motors Party" on Christmas Eve, 1928. Regular

programming began shortly thereafter, and western listeners could now

enjoy the original eastern productions for the first time. NBC now

boasted a nationwide network of 58 stations, with the potential to

reach 82.7% of all U.S. receivers.[8]

With the inauguration of the new transcontinental service, the process of duplicating the programs of the eastern networks in San Francisco was discontinued. Because only one circuit had been installed, however, the Red and Blue networks could not be fed simultaneously. Instead, a selection of the best programs from both networks was fed to San Francisco, where they were relayed to the western affiliate stations. Thus, the Orange Network continued to exist, although in name only.[1]

Even though the duplication of programs was no longer needed, the Western Division staff was not dissolved. It continued to produce additional programs for western consumption only, which were used to augment the eastern schedule. In addition, the trans-continental line would occasionally be reversed, and programs produced in San Francisco would for the first time be fed eastward to the rest of the nation.[1] The first nationwide broadcast from the West Coast had been the Rose Bowl Game from Pasadena on New Year's Day, 1927, with Graham McNamee at the microphone.[5] But, this had been accomplished on a temporary hookup over normal phone lines. The first regular coast-to-coast broadcast from the West over high-quality lines took place in April of 1930, with the broadcast of the "Del Monte Program" sponsored by the California Packing Company. Other programs quickly followed. Soon the San Francisco staff was bigger than ever, simultaneously producing programs for local broadcast over KGO and KPO, for the Western hook- up, and for nation-wide consumption. All of these production activities were further complicated by the time difference between the East and West Coasts. This meant that a program for broadcast in the East at 7 p.m. would have to be performed in San Francisco at four, and then repeated three hours later for western audiences. Thus, it was not uncommon to have all three San Francisco studios in use at once: one producing a program for the East Coast, another for the West Coast, while a third was producing for one of the local stations.[1]

NATIONAL PROGRAMS ORIGINATE IN SAN FRANCISCO

Several programs produced in San Francisco within the next few years

quickly gained nationwide popularity. Programs such as "Death Valley

Days", "The Demi-Tasse Revue", Sam Dickson's "Hawthorne House" and

many others became nationally known. Dickson was one of

San Francisco's best-known radio writers. He got his start there in

the twenties at KYA, writing shows that featured the station manager

and the switchboard operator as principal characters. In 1929,

Dickson conducted a survey for the Commonwealth Club about radio

advertising. Broadcast advertising had not yet come into its own, and

there were many who voiced objections to radio being put to such a

use. Dickson's survey was revolutionary, in that it discovered 90% of

the city's radio listeners did not object to commercials, providing

they were in good taste; and, virtually all of them actually said they

patronized the few advertisers that were then on the air. The results

of Dickson's survey were indeed revolutionary, but they also prompted

a revolution he didn't expect -- he was blacklisted by every station

in town![9]

Sam Dickson fought the blacklisting as best he could. He was still doing some writing for KYA, and managed to do some writing for NBC under an assumed name. By the time NBC discovered his true identity, however, his work had become admired to the point where he was allowed to remain as a staff writer. He wrote scripts for many programs in the ensuing years, including two popular series, "Hawthorne House" and "Winning of the West", as well as police stories and biblical stories for children. He continued with NBC as one of its most prominent writers up into the sixties, and in later years was the author of "The California Story", a series heard on KNBC (formerly KPO, now KNBR) for a quarter century.[9]

Several other San Francisco programs were nationally known. One was

"Carefree Carnival", sponsored by the Signal Oil Company. This was a

program of western music and skits broadcast from the stage of the

Marines' Memorial Theater beginning in 1934. It was hosted by home-

spun Charlie Marshall and featured Meredith Willson's Orchestra. The

most famous program to ever originate in San Francisco, however, was

"One Man's Family". This program was a national favorite on radio and

television for 27 years, and was always among the ten most popular

programs in the nation. Its author, Carleton E. Morse, was the

biggest figure in San Francisco radio at the time.

Several other San Francisco programs were nationally known. One was

"Carefree Carnival", sponsored by the Signal Oil Company. This was a

program of western music and skits broadcast from the stage of the

Marines' Memorial Theater beginning in 1934. It was hosted by home-

spun Charlie Marshall and featured Meredith Willson's Orchestra. The

most famous program to ever originate in San Francisco, however, was

"One Man's Family". This program was a national favorite on radio and

television for 27 years, and was always among the ten most popular

programs in the nation. Its author, Carleton E. Morse, was the

biggest figure in San Francisco radio at the time.

CARLETON E. MORSE

Morse was a "California transplant", born in Louisiana June 4, 1901,

and relocated to California at the age of 16. Morse led a farm life as

a child, and was the first of six children born to George and Ora Morse

in Jennings, Louisiana. At the age of five, he and his family moved

to a fruit ranch outside of Talent, Oregon, a town which Morse described

as "a little wide place in the road". He lived on this ranch until 1917,

when his father became the superintendent of a rice mill in Sacramento.

"When we left the ranch," he later wrote, "I determined that never in my

life again would I return to ranch life ... I would starve to death

on a city street."

After graduating from high school in Sacramento, Morse came to the Bay

Area to attend the University of California at Berkeley. After two and

a half years there, he decided that college was not for him and he

returned to Sacramento, where he went to work as a reporter for the

Sacramento Union. A year and a half later, in 1922, he went to the

San Francisco Chronicle. The following three years saw him move in quick

succession to the San Francisco Illustrated Daily Herald, Seattle Times,

Vancouver Columbian and the Portland Oregonian, before returning to San

Francisco in 1928. It was there, while working at the San Francisco

Bulletin, that he met a fellow staff member named Patricia Pattison

De Ball. They were married September 23, 1928.

After graduating from high school in Sacramento, Morse came to the Bay

Area to attend the University of California at Berkeley. After two and

a half years there, he decided that college was not for him and he

returned to Sacramento, where he went to work as a reporter for the

Sacramento Union. A year and a half later, in 1922, he went to the

San Francisco Chronicle. The following three years saw him move in quick

succession to the San Francisco Illustrated Daily Herald, Seattle Times,

Vancouver Columbian and the Portland Oregonian, before returning to San

Francisco in 1928. It was there, while working at the San Francisco

Bulletin, that he met a fellow staff member named Patricia Pattison

De Ball. They were married September 23, 1928.

In 1929, the Bulletin was absorbed into the San Francisco Call to become part of the Hearst empire, and Carleton Morse was out of a job. He didn't know it at the time, but he had just ended his newspaper career.

A strange fascination with radio broadcasting had come about in the last year for Morse, and his face was frequently seen in the NBC window at 111 Sutter Street. He began casually taking notes on how he thought the NBC programs could be improved. And, when he was released from the Bulletin, Morse applied for a job with NBC. He later told of how he was hired:

They had a show coming in from New York -- it was called

"The House of Myths", dramatizations of Greek classics.

They said, "We can't do these -- they're terrible. Can you

take them and rewrite them, or dramatize some myths that we

could produce?" So, they sent me home and I conceived the

idea of doing the myths in modern vernacular with a heavy

... tongue-in-cheek innuendo on the sex life of the Gods ...

As he readied his script for NBC, Morse received a job offer from the

Seattle Times. Faced with a crossroads decision, he decided the new

medium of radio would be much more exciting, so he quickly polished his

work and returned to the NBC offices, script in hand. Ten minutes later

he was hired, just two weeks before the stock market crash of 1929.

Morse found writing for NBC most rewarding. In a later radio interview, he said:

During those days, the thing that was so very pleasant was that

there were no standards of writing. You were turned loose to

think of something and do it. And out of this maelstrom of

confusion came many of the shows that later developed into

Coast and National shows. It was a wonderful time. It was a

new era in a new medium and everybody has his opportunity.

He started out by continuing with the "House of Myths". The program

got very good listener response on the Coast, although it drew little

reaction in the East, where it was also performed for a while. When

that series ended, he dabbled in several other ideas, all without any

significant listener response. However, he received marked response

when he tried his hand at mysteries. Several popular mystery series

followed: "The Witch of Endor", "The City of the Dead", "Captain

Post: Crime Specialist", "The Game Called Murder", "Dead Men Prowl",

and others. Especially well liked were a series of four programs

based upon the files of the San Francisco Police Department,

"Chinatown Squad", "Barbary Coast Nights", "Killed in Action" and

"To the Best of Their Ability". San Francisco Police Chief William J.

Quinn worked closely with Morse in the writing of these episodes, and

narrated all four series.

ONE MAN'S FAMILY

By 1932, Carleton E. Morse was the biggest name in radio drama on the

Coast. But, he had tired of the continual diet of murder and violence.

As an antidote to this, he began working on a series he called "One Man's

Family". Morse was appalled by what appeared to be a coming deterioration

of the family life style in America. He later told an interviewer:

After the First World War, there was a beginning of a

deterioration of the family, of parent-child relationships.

I had been brought up with very strict, conventional home

life, and it rather appalled me to see what was going on.

He decided to write a series giving "a down-to-earth, honest picture of

family life". Further influenced by John Galsworthy's "Forsythe Saga",

he began working on pilot scripts for "One Man's Family".

"One Man's Family" told the story of the Barbour family, an affluent, moral family residing in the Sea Cliff district of San Francisco. This series did not fit into any previously-used program formulas -- it was unlike anything that had been done on radio up to that time. It simply told the story of everyday life in a model family. Morse hoped it would become popular because the public would identify closely with its characters.[1]

He took four pilot scripts to the production manager of the San Francisco network operation, who soon came to Morse with them and said, "It's quite apparent that you're written out. This would never go, and I suggest -- why don't you resign from NBC?" Morse was taken aback by this comment, but he felt a personal grudge against him might be the real issue, instead of the quality of his scripts. So, he took them to Don Gilman, head of the West Coast operation. Gilman read the scripts, liked them, and approved them for production over the objections of the production manager. "One Man's Family" was on its way.

The program made its debut on Friday, April 29, 1932. It was carried from 9:30 to 10:00 p.m. on just three stations, in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle. However, after the first few episodes, the other West Coast stations requested that the program be opened to the entire network.[10]

Western listeners responded to the program almost immediately, and

their response was overwhelming. "One Man's Family" quickly became

one of the most listened-to programs on the coast. However, the story

concept was new, and companies were reluctant to sponsor it. After

almost a year as an unsponsored feature, an announcement was made at

the end of an episode that NBC was considering dropping the program,

and that audience response was being solicited. The thousands of

letters that swamped the mail room overwhelmed everyone, especially

Morse. In a final, desperate attempt to woo a sponsor, the Sales

Manager hired a suite of rooms in one of San Francisco's posh hotels

and scattered the many letters over the floors, furniture, and every

other horizontal surface. After wining and dining officials of the

Wesson Oil Company in the hotel dining room, he took them up to the

suite, where he showed them the scene and invited them to read just

one letter. Needless to say, they bought the series; Wesson Oil and

Snowdrift became the sponsors of "One Man's Family" January 18,

1933.[10]

Western listeners responded to the program almost immediately, and

their response was overwhelming. "One Man's Family" quickly became

one of the most listened-to programs on the coast. However, the story

concept was new, and companies were reluctant to sponsor it. After

almost a year as an unsponsored feature, an announcement was made at

the end of an episode that NBC was considering dropping the program,

and that audience response was being solicited. The thousands of

letters that swamped the mail room overwhelmed everyone, especially

Morse. In a final, desperate attempt to woo a sponsor, the Sales

Manager hired a suite of rooms in one of San Francisco's posh hotels

and scattered the many letters over the floors, furniture, and every

other horizontal surface. After wining and dining officials of the

Wesson Oil Company in the hotel dining room, he took them up to the

suite, where he showed them the scene and invited them to read just

one letter. Needless to say, they bought the series; Wesson Oil and

Snowdrift became the sponsors of "One Man's Family" January 18,

1933.[10]

Soon after, on May 17 of that year, the program became one of the first San Francisco programs to be piped through the trans-continental line to the East, where it was heard nationwide for the first time. Wesson Oil sponsored the Western production, while the version heard in the East was sustaining, or unsponsored. Separate scripts had to be utilized for nearly eight months, until eastern audiences could catch up with the story line and the two productions could be consolidated. [10]

The nucleus of the cast, the four main characters, were portrayed by the same actors for the entire 27 years the program was heard on radio. They were: Father Henry Barbour, played by J. Anthony Smythe; Mother Fannie Barbour, played by Minetta Ellen; Paul Barbour, who was played by Mike Raffetto; and Hazel, portrayed by Bernice Berwin. Other characters were the twins, Clifford and Claudia, played by Barton Yarborough and Kathleen Wilson, and Jack, who was played by Page Gilman (son of Western Division head Don Gilman). All of these actors had been hand picked by Morse at the start of the program. In fact, each charactcer had been created specifically with the actor in mind, encompassing his own personality traits so that, as Morse put it, they could really "get into their own parts".

Morse wrote all of the scripts himself at first, and insisted on directing each of the productions as well. After the first several years, Mike Raffetto frequently substituted for him, directing and writing while he was away. In later years, Harlan Ware wrote many of the scripts.

On a typical day, Morse would leave his rambling home in the Skylonda district of the San Francisco Peninsula, and be in his office hard at work by 5 AM. He preferred to do his writing at this time, when there was no one around to bother him. By the time the rest of the NBC staff arrived, he had already finished his daily script and would turn to the task of directing, producing and casting for the program. Morse claimed that he could do his writing only in seclusion. He said he would go into an almost trance-like state, to the point where he would actually experience the situation in his mind, and the words would just flow onto the typewriter pages automatically. He said, "I would just sort of lose consciousness until I finished." If anyone would interrupt him in the middle of this process, he would usually have to scrap all that he had written and start again from scratch, as he found it impossible to pick up the thread of his thoughts. After he finished his script, he would hand it in, unread, to be typed, and would have completely forgotten what he had written until he received it at his director's chair. He would make any necessary revisions at that time.

The production of the program was complicated by the partial sponsorship problem. In 1934, the program was being performed three times: Fridays from 7:30 to 8:00 PM for the Mountain and Central time zones; 8:15 to 8:45, sponsored by Wesson Oil for the Pacific Coast; and again the next day at 5:30 for Eastern listeners. This complicated things to the extent that the West Coast Manager Don Gilman began looking for a full-time, nationwide sponsor. He found it in Kentucky Winners Cigarettes. The program was moved to Wednesday nights, and Kentucky Winners began sponsoring "One Man's Family" November 21, 1934.

The short sponsorship of Kentucky Winners is a good example of public morals in the thirties, and of the power of the broadcast audience. Joan Buchanan wrote in a "Radio Life" article:

The minute the (first) commercial was over, long distance phone

calls and wires began to pour in, protesting the use of such a

product in connection with a wholesome, family program.

The public outcry was so great that the sponsor cancelled after only ten

weeks on the air. The program was moved again, this time to Sunday

nights, and went nearly two months without a sponsor. Finally, in March

of 1935, Standard Brands, Inc., began a fourteen year sponsorship of the

program, and during the remainder of radio's golden years, "One Man's

Family" would be synonymous with Royal Gelatin Desserts and Tender Leaf Tea.

It was about this time that Morse began tiring of the repetitiveness of "One Man's Family". Just as he had grown weary of continual murder-and- violence stories, he now tired of the sugar and syrup of his latest program. He needed to begin another series that counteracted this effect, and so "I Love a Mystery" was born. "I Love a Mystery" was a childrens' adventure series, featuring the trio of adventurers Jack, Doc and Reggie. It was a national favorite for nearly two decades, and was an NBC feature until network radio's declining years.

PROFOUND CHANGES

NBC took two major steps in 1936 that had a profound effect on Pacific

Coast radio. The first was the opening of a second Pacific Coast

network. Now, for the first time, the entire compliment of programs

from both NBC networks could be heard on a nationwide basis. The

original NBC "Orange Network", with the exception of KGO, became the

Pacific Coast Red Network. KGO, along with KECA Los Angeles, KFSD San

Diego, KEX Portland, KJR Seattle, and KGA Spokane formed the new

Western Blue Network.[11] (The latter three stations had been a part of

the "Gold Network" from 1931 to 1933, after the demise of the Seattle-

based American Broadcasting Company, the first of several networks to

use that name. The Gold Network was discontinued by NBC in 1933 to

save line costs.[12]) The West Coast Blue Network was inaugurated with

the broadcast of the Rose Bowl Game from Pasadena on New Year's Day,

1936.[13]

The second major event of 1936 -- the one that ultimately proved to be fatal for San Francisco's position as a broadcast center -- was the breaking of ground for NBC's new Hollywood studios. This was in response to the American public's increasing desire for West Coast programs. The success of "One Man's Family" and other early coast offerings played a part in this process. But more important was the public's desire to hear their favorite Hollywood movie stars on the radio. Rudy Vallee apparently started the trend in the early thirties. While in Hollywood for the making of a motion picture, he broadcast his weekly program from California and introduced his audience to film star guests.[6] This trend advanced rapidly, and there were no less than 20 network programs released from Hollywood over NBC and CBS during the 1934/35 season.

In the first years of the network, it had been necessary for Hollywood stars to travel to San Francisco to make a broadcast, a requirement that severely limited the frequency of their appearance. This had been necessary because AT&T's broadcast lines fed from San Francisco to Los Angeles, and not the other way around. Programs were fed nationwide from city to city on a serial hookup, and Los Angeles was the end of the line. In order for programs to be fed nationally from Los Angeles, they would have to be fed eastward by a separate circuit to Chicago, where they could connect into the network. When Eddie Cantor moved his "Chase and Sanborn Program" to Hollywood in 1932, this aspect added $2,100 per week in line charges to the program's budget.[14]

The limitations of the AT&T network began to be overcome in 1936, under pressure of the network's desire to satisfy the public's taste for Hollywood programming. The new circuit that was constructed to bring the Blue Network to the coast in 1936 terminated in Los Angeles instead of San Francisco. Further, AT&T had incorporated a new system called the "quick reversible" circuit. Under this arrangement, the operation of a single key would reverse the direction of every amplifier in the line between Los Angeles and Chicago, so that the same line that formerly fed westward could now move programs from west to east. The circuit could be completely reversed in less than 15 seconds, well within the time of a station break.[15] Thus in 1936 it became economical to produce national programs in Hollywood on a wide scale for the first time. Big Hollywood names like Al Jolson, Bob Hope and Clark Gable were regularly heard on NBC after that year.

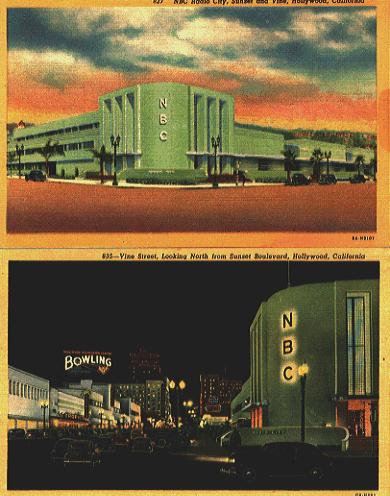

The new NBC Hollywood studios officially opened for business October 17, 1938. Sprawling over a 4-1/2 acre tract at Sunset and Vine, the $2 million facility became the new Western Division headquarters for the network. The West Coast executive offices that had been divided between San Francisco and Los Angeles were consolidated in a new three story executive building. There were eight studios, including four auditoriums that seated 350 persons each, the largest ever constructed for radio.[16]

The opening of the Hollywood studios and improvements to the AT&T

leased line system marked the beginning of a gradual exodus that, over

a five-year period, saw virtually all of San Francisco's network

programming move to Hollywood. By 1942, only a skeleton crew remained

to program the local stations. One of the first programs to leave was

San Francisco's beloved "One Man's Family". Production of this

program was transferred to Hollywood in August of 1937, even before

the new studios had been completely finished. The first program from

Los Angeles aired October 8.[10]

The opening of the Hollywood studios and improvements to the AT&T

leased line system marked the beginning of a gradual exodus that, over

a five-year period, saw virtually all of San Francisco's network

programming move to Hollywood. By 1942, only a skeleton crew remained

to program the local stations. One of the first programs to leave was

San Francisco's beloved "One Man's Family". Production of this

program was transferred to Hollywood in August of 1937, even before

the new studios had been completely finished. The first program from

Los Angeles aired October 8.[10]

(The program's author, Carleton E. Morse greeted the move with great displeasure, and he kept San Francisco as the locale of the program after the move. This bothered some Los Angeles area residents. Morse received a letter from the Los Angeles Junior Chamber of Commerce which deplored the fact that such a popular Los Angeles production had its locale as San Francisco. They politely invited the Barbour family to move to Southern California. But Morse declined, and the Barbours continued to live in San Francisco until the series finally closed in 1959.

RADIO CITY

For a while, NBC intended to operate equal personnel and artist staffs

in both cities.[17] To that end, NBC began to draw up plans for an

elaborate new studio building in San Francisco to replace the outmoded

facility at 111 Sutter Street and match the opulence of the new

Hollywood facility. This was NBC's "Radio City", which drew national

acclaim for both its architectural and broadcast features. And it was

built by mistake.

Plans were drawn up and bids taken in 1940 for the construction of an ultra-modern four-story studio complex at Taylor and O'Farrell Streets. Meanwhile, NBC apparently changed its mind and decided to move all the remaining operations to Hollywood. According to one story, the ground breaking was set to begin when the West Coast vice president received a telegram from New York. It said a decision had been made to phase out the San Francisco operation, and that the new building must not be built. But, it was too late; the event, once set into motion, could not be reversed. The vice president himself officiated at the ground breaking ceremony that day, the telegram in his pocket.

The million dollar facility was formally dedicated April 26, 1942.18

It was an impressive edifice, four stories of pink, windowless walls

with layers of glass brick outlining each floor. Over the marquee, at

the main entrance to the building, was a three-story mosaic mural

designed by C. J. Fitzgerald which depicted different facets of the

radio industry. Inside, facilities included a 41-by-72 foot main

studio, two 24-by-44 secondary studios, and four smaller studios. In

addition, a parking garage occupied practically the entire first

floor. One of the smaller studios, Studio G, was equipped with a

false fireplace, fur rugs and comfortable furniture. It was reserved

for V.I.P. guests exclusively, and Harry Truman, General Sarnoff and H.V. Kaltenborn were just a few of those who eventually used it.

Another feature of NBC's radio palace was a roof garden where Sam

Dickson, Dave Drummond, James Day and other staff writers would

produce scripts in their swimsuits and work on their suntans at the

same time.[19]

The million dollar facility was formally dedicated April 26, 1942.18

It was an impressive edifice, four stories of pink, windowless walls

with layers of glass brick outlining each floor. Over the marquee, at

the main entrance to the building, was a three-story mosaic mural

designed by C. J. Fitzgerald which depicted different facets of the

radio industry. Inside, facilities included a 41-by-72 foot main

studio, two 24-by-44 secondary studios, and four smaller studios. In

addition, a parking garage occupied practically the entire first

floor. One of the smaller studios, Studio G, was equipped with a

false fireplace, fur rugs and comfortable furniture. It was reserved

for V.I.P. guests exclusively, and Harry Truman, General Sarnoff and H.V. Kaltenborn were just a few of those who eventually used it.

Another feature of NBC's radio palace was a roof garden where Sam

Dickson, Dave Drummond, James Day and other staff writers would

produce scripts in their swimsuits and work on their suntans at the

same time.[19]

The building was a magnificent tribute to the state of the art. It was also San Francisco's last great fling as a radio center, for less than a year after its completion the southward exodus had ended, and most of the facility stood unused except for an occasional network sustaining feature. In the ensuing years much of the building was leased as office space, and the entire radio operation consisted of a disc jockey playing records in a third floor booth. KGO was moved to Golden Gate Avenue in the early 1950's, and KPO, by then known as KNBR, moved out in 1967. That was the year the building was sold to Kaiser Broadcasting Company, and it became the new home of KBHK Television. At last, it finally began to see extensive usage for the purpose for which it was built.[20]

REFERENCES:

[1] Interviews by author with Bill Andrews, former NBC announcer; San Francisco, 10/13/70, 11/2/70, 4/1/71. [2] Archer, Gleason L., Big Business and Radio (American Book-Stratford Press, Inc., 1939). [3] Broadcast Weekly Magazine, 8/24/29, page 6. [4] San Francisco Chronicle, 4/1/27. [5] Shurick, E.P.J., First Quarter Century of American Broadcasting (Midland Publishing Company, 1946), page 163. [6] Ibid., page 416. [7] Manuscript: "Special to Radio Guide", by Louise Landis, Feature Editor, NBC, 111 Sutter Street, San Francisco, May 16, 1934; from KGO's history file. [8] Spaulding, John W., "1928: Radio Becomes a Mass Advertising Medium", Journal of Broadcasting, Vol. VIII, No. 1 (Winter 1963-64), page 31- 44. [9] "Scoop", San Francisco Press Club, 1970. [10] Sheppard, Walter, "One Man's Family -- A History and Analysis", unpublished doctoral dissertation, the University of Wisconsin, 1967; supplied by Carlton Morse. [11] Broadcasting Magazine, 1/1/36. [12] Broadcasting Magazine, 11/1/31, 4/1/33. [13] Press Release, "NBC Inaugurates Second Nationwide Network", 1936; from KGO's history file. [14] Higby, Mary Jane, Tune In Tomorrow, (Cowles Education Corporation, 1966), page 22. [15] de Mare, George, "And Now We Take You To -- !", Western Electric Oscillator, December, 1945, page 10. [16] Broadcasting Magazine, 11/1/38. [17] Broadcasting Magazine, 1/1/37. [18] Radio City souvenir dedication brochure, 4/25/42. [19] Roller, Albert F.,"San Francisco's Radio City", Architectural Record Magazine, November 1942. [20] San Francisco Examiner, 12/6/67.

© Copyright 1997 John F. Schneider. All rights reserved.

For better views of the photographs, see the Photo Archives section of this website.

[Go to Index of Articles] [Go to Photo Archives] [Return to SF Home Page]